Bik Van der Pol

Do You See the Signal?

Vision and Seeing

What is it that makes someone see or not see? Is seeing strategic? Is the refusal to see ignorant? What do we see if we turn a blind eye? Are we then willfully blind, or do we just believe what we see? How do we know that what we are seeing or not seeing is just, or even real? Who or what makes us see what we need to see? What do we miss when we do, or do not see?

Before we begin let us ponder, rest, sit a bit, and create some space, so to speak, in order to move into questioning these faculties.

The School of Missing Studies started in 2003 as an initiative of a small group of artists, thinkers, and architects.1 Observing the disappearance of public spacemissingã as a matter of urgency and conceived an informal, organic, nomadic, collaborative platform for experimental study and research from which to ask the question: Whose field of vision are we seeing? This school, a process-oriented and site-sensitive project, is an attempt to amalgamate different forms ofãoften overlookedãknowledge, challenging anyone involved to move beyond their existing geographic and culturally based discourses, situations, and disciplines. Investigating what culture(s) laid the foundations for the loss we are experiencing from modernization and how this loss can talk back to us as a potential site of learning, the School of Missing Studies envisions a space where learning and experiences are anticipated in a continuously changing dynamic, where making public and public making are inherent to the workings of the project, and where ideas also have to be taken into action.

Contrary to models whereby publics emerge organically, at the heart of modernity lies the concept of the blueprint that imposes structures to configure or reconfigure social relations; this blueprint is to be considered as the ultimate modernist endgame.2 But where do models fail? What is lost when we move from the scale of the blueprint to that of the planet? Convinced that we need to stretch learning (as an active process) beyond what is usually taught, the School of Missing Studies is calling for a space for loose improvisation, a space to turn existing knowledge against itself as a method for learning to think autonomously, to affect our capacity to see things otherwise, to trust that seeing and to set oneãs own pedagogical terms. The creation of this space requires a continuous journeyãthrough different case studies, fieldwork, and readings both in and outside the field of educationãof encounters with other perspectives and sensibilities (including, but not limited to geo- and biopolitics, urban planning, and architecture), to incite a continuous process of learning in an expanded field.

Activities of the School of Missing Studies have included, among others, Teasing Minds (2004), a project based on a statement of neuropsychologist Ernst PûÑppel thatãalthough perfectly equipped to register differencesãif the human brain is not sufficiently challenged, it will show a natural tendency to act conservatively, the logic of which was coupled with inquiries into cultural and urban developments in Munich.3 Twist to Wild Life (2004) focused on the shrinking cities in East Germany as a recent occurrence that could extend to other parts of Europe; shaped as a workshop it enticed us to develop possible scenarios for a cultural turn that should not be misinterpreted as a loss or threat, but as a possibility.4 The Lost Highway Expedition (2006) was a road trip along the unfinished ãHighway of Brotherhood and Unityã in former Yugoslavia to retrace and study the relationships that got lost due to the Yugoslav Wars, at the microlevel of friendships, family, communities, and institutions, to articulate and imagine the evolution of new and transforming borders and territories of Europe, and to speculate on the unknown future of Europe as a union.5,ã Azra Aksamija website, accessed February 13, 2017, www.azraaksamija.net/projects-6.] A Particular Site as a Lens for Speculation (2015) invited participants to engage in a collaborative process incorporating the many disparate languages with which a harbor ãconverses,ã where each stage in the reception, processing, and distribution of goods comes with its own syntax, vocabulary, and infrastructure.6 The departure points for this narrative were the utilization of silence as a political imperative of infrastructure, and the role that silence will play in the future harbor, both in its human and automated state; for some, automation threatens the future presence of human voice(s) in the harbor (that, as a result and consequence, is ãliberatedã from human labor). For others, the future harbor is a utopian site where humans are emancipated from the location itself, leaving the harbor silent albeit speaking in inaudible code, the engineered and remote-controlled language of infrastructure.

Invited to develop a Temporary Master Program from 2013 to 2015 as part of the Sandberg Instituut, we brought the School of Missing Studies inside the university. We rallied together students, scientists, artists, and activists, and occasionally scholars from other universities and organizations, along with members of the general public who became involved in different parts of the program. The program itself we loosely structured as an ãarchipelago,ã an extensive group of islands formed by both water and land. Analogous to this image of the archipelago, the program was perceived as a scattered but cohesive landscape of key areas considered to be connected in their relationship that would create spaces of experience to navigate and traverse. A space where the ãin-betweenã is as important as the islands themselves ... a space that would formãwe imaginedãnothing less than an attempt to see, sense, listen, and understand what is missing ... an archipelago against relational fragmentation, while being fragmented spatially, and in time. Different practitioners from different backgrounds and disciplines were invited to each take hold of an island, taking their practice and urgencies as points of departure during intense work periods with students. These ãisland keepersã are working in and between areas of the arts, culture, urbanism, technology, and politics, in a fragmented archipelago that is undivided; as it is within the spaces in their close proximity to each other that they become what they are. Areas, in relation, produce spaces to think and act.

Bik Van der Pol

Do You See the Signal?

On expedition with Rios e Ruas to explore and recognize the existing 300 hidden rivers underneath the streets of SûÈo Paulo. Rio e Ruas aims to create an affective comprehension of urban space, and to see what kind of city will be left for the next generations (image: Bik Van der Pol)

This School of Missing Studies began in Nagele, a Dutch modernist agrarian settlement in the Noordoostpolder and an exemplar in the modernist era of archetypically Dutch architectural planning for and modification of society. This small town and the Noordoostpolder at large, which was entirely built on man-made land reclaimed from the sea, fit perfectly into the modernist vision that architecture, applied as an economic and political tool, could improve the world through design, thus providing fertile ground for us to reflect on the effects of modernity on a local and global scale. Nagele was designed by the architectural team De 8 and presented at the CIAM 8 meeting in 1956.1 The planning of the Noordoostpolder shows a highly rationalized grid of roads, canals, cities, agrarian land, and forests, and the structure of Nagele must be understood in relation to the overall system of the polder. Important territorial principles in structure, form, and landscape can be seen in the project of Nagele; as such, Nagele can be seen as an early blueprint for the continuing transformation of the urban environment that is currently extending over the entire planet.

Bik Van der Pol

Do You See the Signal?

Fernanda Curiãsô workshop seriesô Projeto ClimaIbirapuera.ô As part ofô Turning a Blind Eye, Projeto ClimaIbirapuera brings together theory and practice over Parque Ibirapueraãs extended territory, which has been fragmented, appropriated, and misused over the last six decades. The workshop series includes archival documentation of the park and surrounding institutions and on-site observations, while investigating systems of mapping, infrastructure, and economics, and how green spaces appear and get lost in cities, territories, and ecologiesô (image: Bik Van der Pol)

From there, with the help of different island keepers, the School of Missing Studies navigated from fragmented cartographies to the exploration of territories that no longer border Europe, but have expanded (in light of increasing globalization and international capitalism) into our immediate surroundings, as well as spilled outward and far into the African continent, to take one example among many others. We investigated what possible ways the concept of ãbarbarismããin the context of rhetoric, aesthetics, and politicsãsurrounds the questionable application of the term ãcrisis,ã and brought the meaningful reality of a destabilizing absence into confrontation with what such a loss means, both for certainties that we may have considered as fundamental, and for our sense of being. Artistic and political abstraction, fragmentation, and think tanks were brought to the table, and we went through moments of exposition that in turn set off experimentation, and the process of experiencing how community is formed at the margins, in the academy, and in unknown territories. The commons were a starting point for thinking and experiencing new possibilities for the concept and use of space and time. A juxtaposition of the early modernist blueprint of new towns with the concept of current and future urban idealsãto make denser, greener, and more pleasant cities that offer a high quality of life to their inhabitantsãwas developed by the students into a role-play and grim game for the speculative construction of a deregulated zone. The recognition of unknown kinds of human knowledge together with knowledge of other life-forms and their poetics, without fully envisaging or knowing where that practice might take us, led to close listening to understand the role of the voice in law in the face of new regimes of border control, algorithmic technologies, medical sciences, and modes of surveillance.

Being part of a two-week long encounter between six artists, curators, and writers and eleven Indigenous Yanomami of the Amazonia forest had significantly affected our own view on site-sensitive knowledge, and was, as a kind of ãlead-in,ã of extreme relevance for us and for how we further developed the program of the School of Missing Studies.1 The practice of mutual learning as a method of exchange formed the basis for the discussions on what learning could be in specific contexts, there, in that forest. We began to collectively ask the question of: What do people need to know in the forest? What agency can be taken in this forest? What kind of knowledge do the children who live in this forest need? What responsibilities do we all have for our different but interrelated contexts? It is hard to overestimate the importance of the presence of the Yanomami and other Indigenous groups in Amazonia for the survival and ongoing biodiversification of this vast forest-land. Knowledge quickly fades from our memories if it is not an active part of daily life and use, and this loss accelerates with the advent of new technologies and a reliance on digital storage to retain and retrieve data. In the case of Indigenous knowledge, lost knowledge is really lost, erased, so to say, as the space in which it is created and practiced, the complex ecosystem of Amazonia is vanishing rapidly through globally accelerating exploitation and the mining of resources by corporations in close collaboration with local governments. Next to the climate change caused by these activities and the loss of other ways of life, intellectual and cultural knowledge such as that based in the human interrelationship with nature, of site-sensitive and extremely specialized learning methods, of the medical qualities of plants, or local languagesãare rapidly disappearing. The Yanomami and the many other groups inhabiting Amazonian territories rightfully insist on voicing their explicit and expert role in this complex ecosystem as cultivators, guards, caretakers, and indispensable carriers of culture, experience, and valuable knowledge. By resisting the governmental demand to bring their children to a school with Brazilian education they refuse to allow them to become ãnormalized.ã In fact, they refuse to participate in an active act of erasure. If we are in agreement that the ideology of capitalist society is fundamental to social control, then education is instrumental in transmitting this ideology; and then education is an ideological state apparatus that helps the ruling ideology continue in order to justify the capitalist system. By deciding that another kind of learning is needed, in their context, where they live, the Yanomami make visible what is missing from ãour world,ã namely, a continuous questioning of what and how, and from whom we want or need to learn.

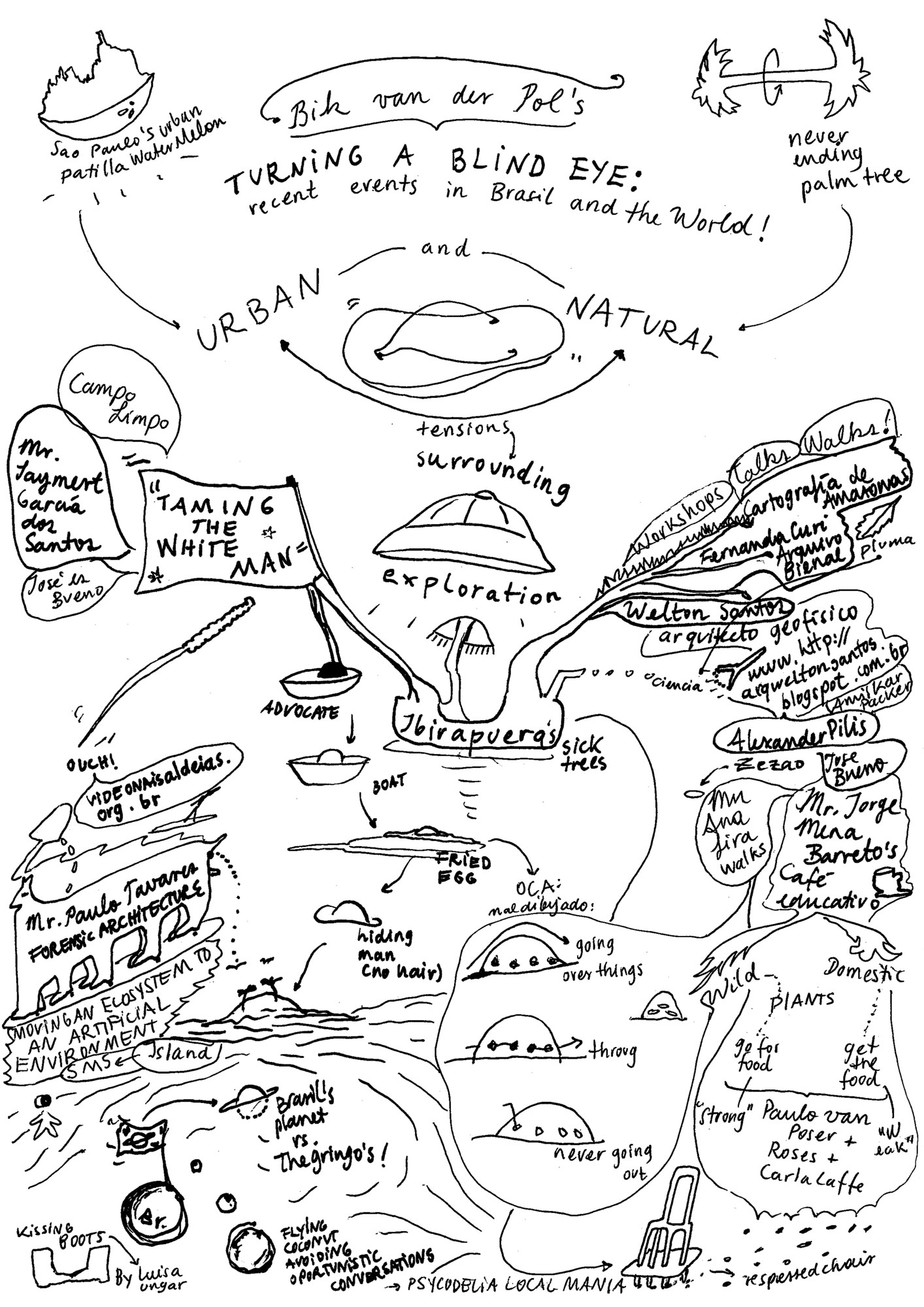

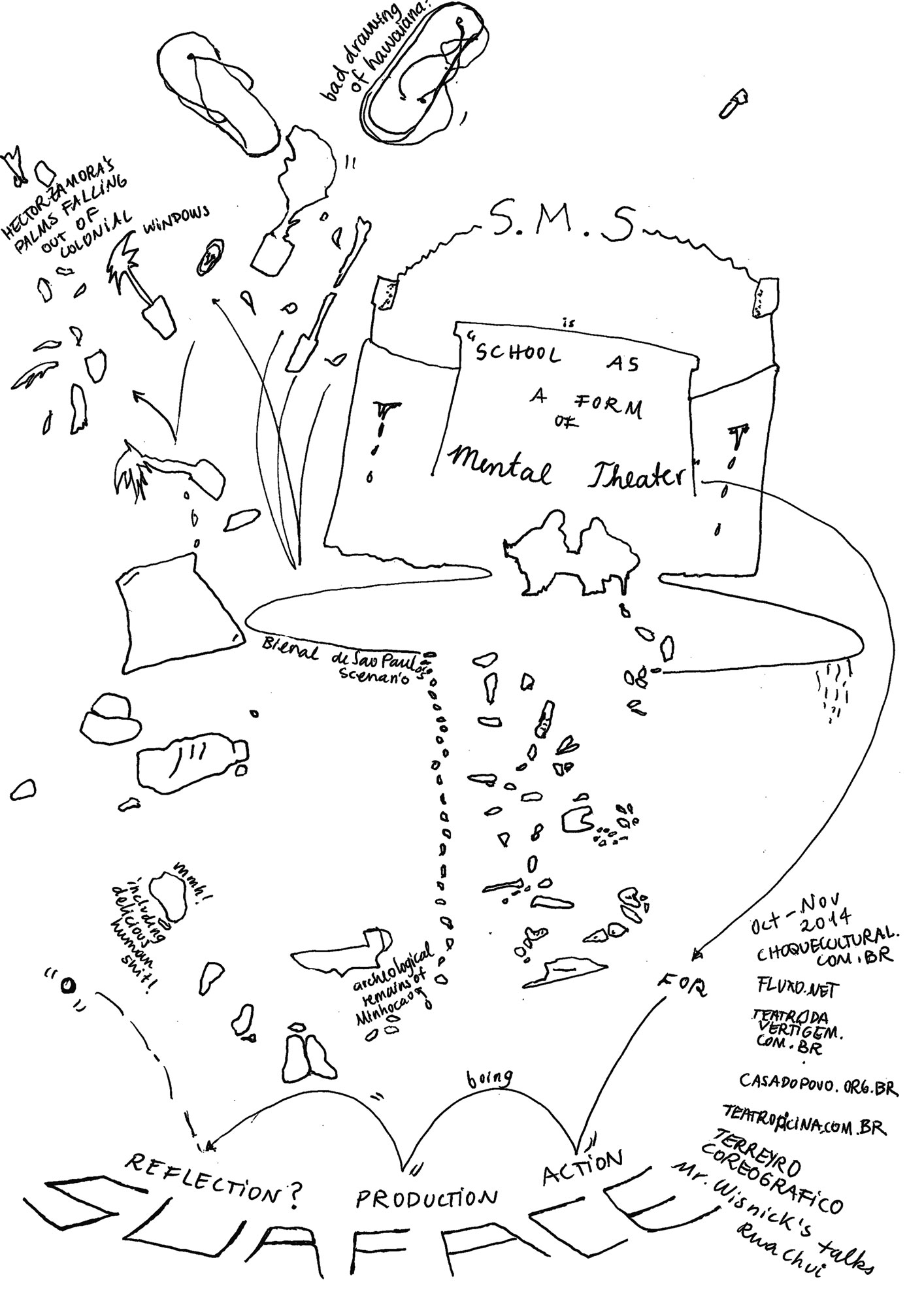

To open up new horizons of action, production, and reflection, and informed by this previous experience, we implemented the educational model of the school as a form of ãmental theaterã into the 31st SûÈo Paulo Biennial,2 shaping that situation to act both as the site of creation and research, as well as an amplifier for solicited responses thus taking practice, as an activity, into the public arena. This project, titled Turning a Blind Eye (2014),3 departed from recent events in Brazil and broader trends worldwide;4 it was also a public program (in which students of the School of Missing Studies and universities, and organizations in SûÈo Paulo were actively involved) shaped as a series of public workshops, interactions, lectures, and ãexpeditions,ã which encompassed the experience of meaning and appearance in a place marked by tensions arising from intense and rapid growth and the corresponding accelerating exploitation of nature. The School of Missing Studies set off to trace, reflect, and register the ãunseenããnot only what we cannot see, but what we will not see, or refuse to see.

So, Do You See the Signal? Really?

Letãs sketch the lay of the land.5 We can all see that we are caught in a period of abrupt transition. Recent occupations of public squares worldwide, the ãcapturingã of private information, the dissemination of counterfeit information, the loss of the boundary between public and private, the large flows of refugees escaping war and climate change demonstrate the urgency of the question of ãthe publicã as a site of conflict over rights, information, access, relations, and objects. It is clear that the fundamental properties of democracy, of sharing space, resources, and means have to be rearticulated, as they appear to be just as precarious as nature in being threatened by a predatory economy. Undoubtedly, changes are taking place, either unseen, or in full light, and perhaps even with a lot of noise added for maximum disarray. Signals hide, but they also appear, often in rupture.

If public spaceneoliberal economic project, by exclusions, privileged access, and disinformation to the point that it is imploding and becoming invisible, a place where it is increasingly impossible to decide what is true or false. Whether public spacepublic spacelearning and (un)knowing toward ways of rehabilitating and sustaining a truly public space

But is public spacepublic spacepublic has been variously located in the domain, arena, realm, sphere, publicity ... showing that the space where ãpublicã manifests itself is not limited to physical space. A space can be defined as ãa continuous area or expanse that is free, available, or unoccupied.ã 8 We propose to define space as that which is being formed, becoming through occurrence, unfolding in terms of its very meaning, which is ãto meet, or meet in argument, to happen, to present itself in the course of events.ã9 Louis Althusser evoked the beautiful image of Epicurusãs atoms that fall like raindrops parallel to each other in the void.10 Nothing happens if these atoms keep falling in parallel, but if they swerveãand no one knows what causes an atom to break the parallelism of its vertical fall in the void and deviate in this almost negligible wayãthey induce an encounter with the atom next to it. From this, a chain reaction may or may not be set off. Encounters are far less predictable than we would like to believe. For changes to not only occur but to take hold, the ãright conditionsã have to be present. Uncertainty is almost a given as not every rupture takes hold; there are, so to say, mistakes, such as revolutions that fail to produce viable changes. And not every encounter fuses in change; most encounters are virtual or utopian, that is, non-encounters. Nevertheless, according to Althusser the encounter is the only way things can move forward. Only then a process of accumulation and change may occur.11 The uncontrolled and unpredictable energy that may result from the encounter orients toward practice: it happens or it does not happen. It is in the encounter that the production of practice occurs, we may say.

Bik Van der Pol

Do You See the Signal?

Drawing made in 2014 by Luisa Ungar after participating in Turning a Blind Eye.

Public spacedemocracy. Like democratic power, public spacepublic spacedemocracy), and that this condition concerns inclusion as much as exclusion, participation as much as privilege; as seeming opposites they work closely together in defining public space

Constant negotiation is fundamental to democracy. It takes endurance and patience, and it is here that it is productive to make a link to art, or artistic practice, as this involves a process of involving repeated exercise in or the performance of an activity or skill so as to acquire or maintain expertise. The performance of different narrations and situations continuously transform what might have been previously thought of as being stable or fixed, into ãa practiced placeã to render visible what ãpublicã could mean and look like, as a form, as an experience where the public becomes manifest, whether through pain, risk, or celebration.2 Society has no pre-given, unifying ground;3 it is found in the process of doing and learning how to continuously form our society on a day-to-day basis.

The School of Missing Studies is practice. Practice to provoke, produce, and invoke spaces of learning as artistic practice in which ideasãthat unite or separateãcan assemble in dialogue4 ... from which they continue to develop and disperse, not as something external, but as a form of an embodied, experienced, ãpassing throughã5 (as they are taken up en passant: art as a political activity) in a process similar to what Jacques Ranciû´re calls the ãdistribution of the sensible.ã Such a practice enacts a symbolic and social transformation by engaging those usually not involved, as we are all implicated, in a shared world; art as a political activity, where the element of ãpassing throughã is essential because it is temporal, suggests action, ritual, and theatricality.

When political and economical forces have come to shape the perception of culture, it should come as no surprise that educationãunderstood as a practice of learning and site of cultural productionãhas fallen behind. If the economic paradigm forces us to retreat from the realm of publicness, then where is the public concerned? How do we move beyond modernism while being fully entanôÙgled in production and consumptionãthe capitalized result of modern times? What practices and approaches are needed to understand what is happening today? What kind of future is already being shaped by many? Is there a future where public spaceart may well be the last niche that continues to carve out this space. If artistic practice has the potential to connect ãthe space of experience to the horizon of expectation,ã6 to produce new meaning and experiences, and significant change in everyday life from unexpected encounters, then it is really time to invest in its place in society. We firmly need to reclaim space for imagination where performing and practicing constitute a ãsocial space where, in the absence of a foundation, the meaning and unity of the society is negotiated, constituted and put at risk.ã7 We need to claim the time to observe, to study carefully, listen, and understand: to insist, stubbornly, on the development of a vocabulary of how to speak, anew. Such an ongoing exercise may not just induce new utopias or distant perspectives, but also may equip people with tools to participate in politics, inspire them to form new or alternative forms of political socialization, to empower them to imagine the world differently, and to act from that.

Reclaiming the space of learning as a public and politically charged space, the School of Missing Studies is a seeding of seeds, and its effects are difficult to estimate. Nevertheless, it is taking as its premise the potential of artistic practice (which is not the territory of artists alone) to create new formations of knowledge and action as a step forward to emancipation. Experiences have a formative effect on how people think, feel, respond, and act. In applying Althusserãs thoughts on space that is not a given, not pre-scripted, but that emerges from practice, from use, that messy and possibly even violent (to shape the future we need to experience the awkwardness of uncertainty), then such a space may have to resist efficiency, functionality, and productivity, because the outcome or product is (and needs to be allowed to be) unsure. When that happens, and a complex process is set in motion that involves unseen correspondences between things and actions, change may hold. Architect Frederick Kiesler noted that ãan object doesnãt live until it correlates.ã8 If artistic practices are a form of organization of relationships between disparate objects and ideas that could point out new significance to conscious audiences, we can perceive its role as laying out the conditions for change. There is no turning away, or back; what we need is to see both forward and backward, to connect pasts and futures. We need multiple visions.

-

The School of

MissingStudies was initiated by Sabine von Fischer, Ivan Kucina, Bik Van der Pol, Milica Topaloviá, STEALTH.unlimited (Ana Déƒokiá and Marc Neelen), Stevan Vukoviá, and Srdjan Jovanoviá Weiss. So far the School ofMissingStudies has taken shape as a workshop, seminar, road trip, temporary masterãs program at a university, a research exhibition, and a residence and performance project, often in collaboration with institutions, biennials, and museums. The School ofMissingStudies resists institutionalization to escape control and formalization, may appear and disappear again, and is organized by different initiators, in different forms. ↩ - Simon Sheikh, ãPublics and Post-publics: The Production of the Social,ã open! (January 1, 2007), www.onlineopen.org/publics-and-post-publics. ↩

- Teasing Minds was initiated by Bik Van der Pol, STEALTH.unlimited architects, and Kunstverein Munich. ↩

- Twist to Wild Life was initiated by Srdjan Jovanoviá Weiss and Bik Van der Pol, as part of the Halle School of Common Property. Results of the workshop were presented at the 6th Werkleitz Biennale in Halle. ↩

-

The Lost Highway Expedition was initiated by Centrala Foundation for Future Cities, and Katherine Carl, Ana Déƒokiá, Ivan Kucina, Marc Neelen, and Srdjan Jovanoviá Weiss for the School of

MissingStudies.See: ãUpcoming: Lost Highway Expedition,ã School ofMissingStudies website, accessed February 13, 2017, www.schoolofmissingstudies.net/sms-lhe.htm; and ãThe Lost Highway Expedition [LHE ↩ -

A Particular Site as a Lens for Speculation initiated by Bik Van der Pol consisted of an open three-month work period at M HKA and AIR in Antwerp with artists, writers, and researchers such as Gia Abrassart, Sol Archer, Common Room, Wiebe Eekman, E. C. Feiss, Fucking Good

Art, Dirk van Lieshout, Martin Schepers, Anja Isabel Schneider, Iffy Tillieu, Jeroen Verbeeck, Kym Ward, Huib Haye van der Werf, and students of the MFA program at the Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam. ↩ -

The Congrû´s internationaux dãarchitecture modern (CIAM, or International Congress of Modern Architecture), founded in June 1928, was responsible for a series of events and congresses arranged across Europe by the most prominent architects of the time. CIAMãs manifesto, one of many in the twentieth century meant to advance the cause of ãarchitecture as a social

art,ã was guided by the principles of modernist planning and was taken up by European governments during the postwar period to mount large-scale urban housing and rebuilding programs. Significantly for the School ofMissingStudies, the activities of CIAM brought together all the main domains of architecture such as landscape,urbanism, and industrial design. ↩ - In 2013 we were all hosted by Anne Ballister, photographer and founder of the Xapomi School at Puraquequara, Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, on a small compound along the Rio MarauiûÀ in the middle of the forest of Amazonia, three days sailing from Manaus. ↩

-

We borrowed this term from Byron, and Bertold Brecht after him, who emphasized the need for a ã

mental theaterã as an activist approach to recast and restage reading, subject, and dialogue within different contextual horizons. From these stagings and restagings a social body of meanings would develop. We apply this as a form for bringing together different voices, experiences, and artistic languages in dialogue. For more onmental theater,seeJerome McGann, ãThe Apparatus of Loss: Bruce Andrewsã Writing,ã in The Point Is to Change It: Poetry and Criticism in the Continuing Present (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007). ↩ -

The expression ãturning a blind eyeã is derived from an anecdote that established the terms ãNelsonian

knowledgeã or ãwillful blindness,ã used in law when a person seeks to avoid civil or criminal liability for a wrongful act by intentionally putting himself in a position where he will be unaware of facts that would render him liable. The British naval officer Admiral Horatio Nelson was notorious for his leadership, strategy, and unconventional tactics. He had also lost an arm and the sight in one eye during combat, contributing to his mythical status. During the Battle of Copenhagen (1801) his cautious commander sent asignalvia the customary system ofsignalflags to Nelsonãs forces, suggesting they withdraw. When the more aggressive Nelson was directed to thesignal, he lifted his telescope to his blind eye and said, ãI really do notseethesignal!ã and continued the attack, risking defeat but resulting in a victory for the British fleet. The winner is always rightãÎ ↩ -

Beginning in April 2013, protests against increases in

publictransport prices in some Brazilian cities grew into large demonstrations against other issues such as widespread government corruption, racism, police brutality, and the funding of major sport events in contrast to decreases in infrastructure, education, health care, and otherpublicservices. By mid-June, the movement had grown to become Brazilãs largest since the 1992 protests, and it continues today. These demonstrations followed the revolutionary wave of the Arab Spring in many countries such as Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, and Turkey. ↩ - Used here to mean the facts of a situation; the way in which the features or characteristics of an area present themselves; the current situation or state of affairs under consideration. ↩

-

Rosalyn Deutsche observed in 1998 that while ã

publicã implies accountability to ãthe people,ã the discourse aboutpublicspaceart, architecture, and urban studies is inseparable from heated debates aboutdemocracyand its crises.SeeRosalyn Deutsche, ãThe Question of ãPublicSpacepublic-space.pdf; and Evictions:Artand SpatialPolitics(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996). ↩ -

See, for example, Simon Sheikhãs thoughts on newpublicformations where action can be taken, in Sheikh, ãPublics and Post-publics.ã ↩ -

Seethe Oxford English Dictionary for this definition of space. ↩ -

Etymologically, ãoccurã originates from ããmeet, meet in argument,ã from Middle French occurrer, from Latin occurrere ãrun to meet, run against, befall, present itself,ã from ob ãagainst, towardã + currere ãto runã (

seecurrent).ãSeeOnline Etymology Dictionary, accessed December 25, 2016, www.etymonline.com/index.php. ↩ - Louis Althusser, ãThe Underground Current of the Materialism of the Encounter,ã in Philosophy of the Encounter: Later Writings, 1978-87, ed. Francois Matheron and Oliver Corpet (London: Verso, 2006), 163ã207. ↩

- Ibid., 185. ↩

- Jacques Ranciû´re, ãThe Aesthetic Revolution and its Outcomes: Emplotments of Autonomy and Heteronomy,ã New Left Review 14 (March/April 2002): 133ã51. ↩

-

Similarly to how Certeau understands practiced place, we would like to emphasize that we understand

art, or rather artistic practice, as a verbãan active act of doingãof practicing: ãIn short, space is a practiced place. Thus the street geometrically defined by urban planning is transformed into a space by walkers. In the same way, an act of reading is the space produced by the practice of a particular place: a written text, i.e., a place constituted by a system of signs.ã Michael de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 117. ↩ -

Claude Lefort,

Democracyand Political Theory (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991). ↩ - Dialogue should not be understood simply as a peaceful matter. Dialogues have coincidental and specific effects as they define the basis and mode of reveal, and with respect to practice are continuously setting conditions to allow or forcefully push the unknown and unseen to appear. Much more than an exchange, dialogue is a constant negotiation between citizens. ↩

-

ãPassing through and dialogue are closely related. Etymologically, dialogue (from the Greek dialogos) means a speech across, between, through two or more people. Dia is a preposition that means ãthrough,ã ãbetween,ã ãacross,ã ãby,ã and ãof,ã and does not mean two, as in two separate entities; rather, dia suggests a ãpassing throughã as in diagnosis ãthoroughlyã or ãcompletely.ã Logos means ãthe word,ã or more specifically, the ãmeaning of the word,ã created by ãpassing through,ã as in the use of language as a symbolic tool and conversation as a medium. Logos may also mean thought as well as speechãthought that is conceived individually or collectively, and/or expressed materially. Consequently, dialogue is a sharing through language as a cultural symbolic tool and conversation as a medium for sharing. The picture or image that this derivation suggests is a ãstream of meaningã flowing among and through us and between us; dialogue connotes a flow of meaning through two or more individuals as a collective, and out of which may emerge new understandings.ã

SeeBela H. Banathy and Patrick M. Jenlink, Introduction to Dialogue as a Means of Collective Communication, eds. ed. Banathy and Jenlink (New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2005), 5. We understand passing through as a moving beyond or crossing through, for example, as making a passage, or as a journey from one place, territory, or body of thought, to another. ↩ -

This phrasing was first coined by Reinhart Koselleck in Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004). He shows that with the advent of

modernity, the past and the future became diverged in relation to each other. Paul Ricoeur goes on unfolding this (in From Text to Action (Northwestern University Press, 2008)), arguing that the space of experience and the horizon of expectation mutually condition each other; while experience never fully determines expectation, and expectation shrinks with the impoverishment of experience, dynamic tension is productive, and potentially enriching. He also argues that a crisis inmodernityis when, instead of a tension, there is a schism between the space of experience the horizon of expectation. ↩ - Deutsche, Evictions, 268. ↩

-

Frederick Kiesler, untitled manuscript (1930s), Kiesler Archive, Vienna, quoted in Lisa Phillips, ãEnvironmental Artist,ã in Frederick Kiesler (New York: Whitney Museum of American

Art, 1989), 114. ↩